Escapade

An Art & About 2010

Associated Event

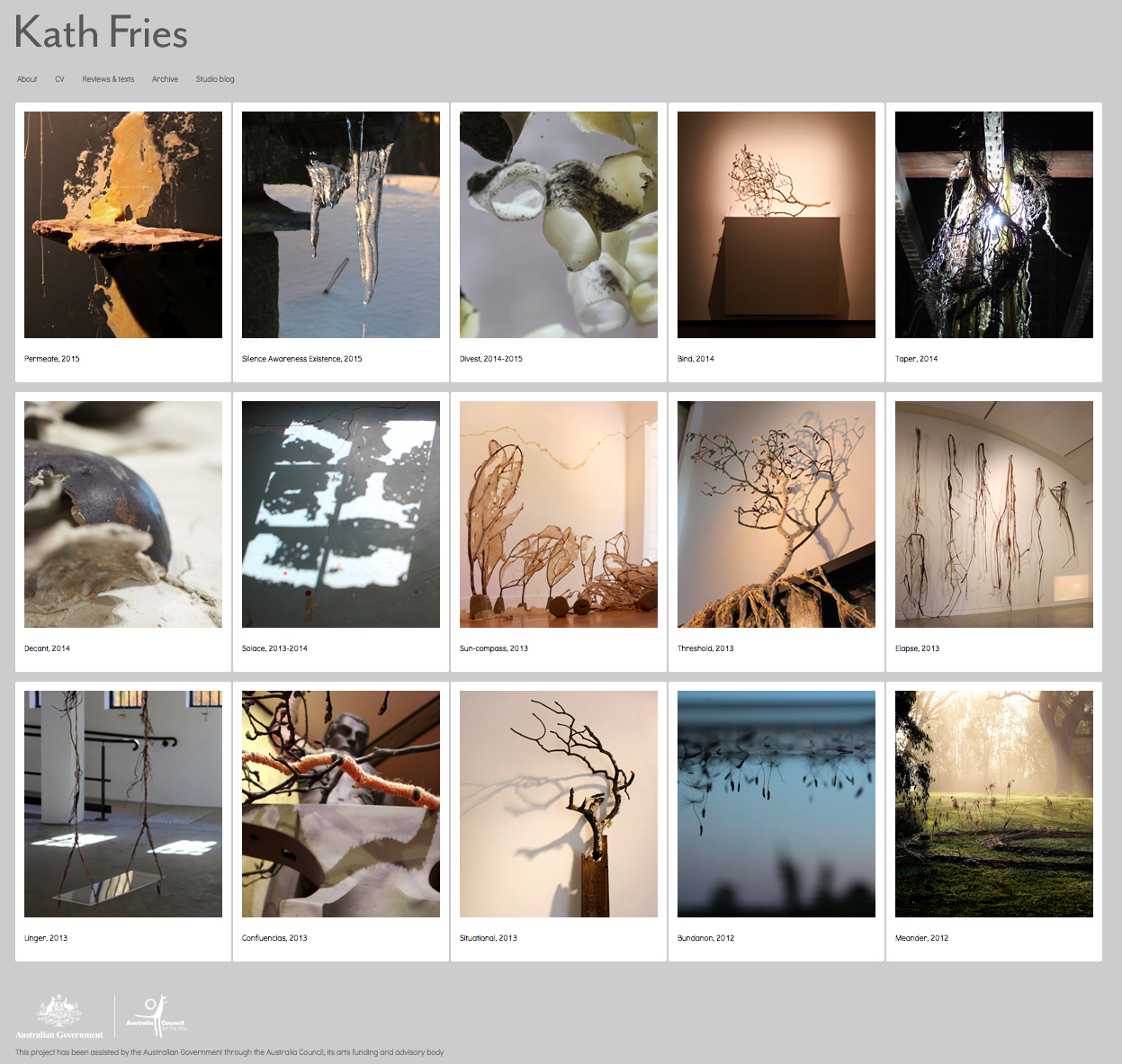

Kath Fries

Gaffa building façade site-specific installation

23 September – 31 October 2010

Referencing the knotted sheets of classic prisoner escape attempts, Kath Fries’ Escapade links this building’s past with the present, by creating a bridge between its former use as police station to its current use as contemporary art spaces.

Referencing the knotted sheets of classic prisoner escape attempts, Kath Fries’ Escapade links this building’s past with the present, by creating a bridge between its former use as police station to its current use as contemporary art spaces. Escapade is a temporary site-specific installation featuring a long red hand-braided rope and white sheeting secured to the flag pole on the roof balcony, trailing down the 1891 heritage-listed façade, coming to a frayed end dangling a few meters above the footpath, illusively just out of reach. 281 Clarence Street was originally built as a police station, which is still evident in the façade's signage, interior levels of surveillance and holding cells; but it now houses Gaffa’s creative contemporary art spaces.

Escapade's red fabric rope was hand-braided using torn lengths of upholstery off-cuts during a weekend backyard group workshop. Many hands and locations have been involved in the progression of this rope artwork. Initially conceived as an indoor installation, leading the viewer through the nooks and crannies of the previous Gaffa Gallery on Randle Street in Surry Hills. Then titled Ariadne’s Thread referring to the ancient Greek myth of the Cretan Labyrinth navigated using a spool of thread. The journey of the hand-braided rope has continued into the outdoors, coiled from the ground up a poplar tree trunk and disappearing into the upper branches, in the Hunter Valley as Recoiling, part of Sculpture in the Vineyards 2009. Earlier this year it was interwoven into the fence rails forming Heart-beat as though echoing the pulse rates of passing joggers on the Drummoyne Bay Run.

Escapade's red fabric rope was hand-braided using torn lengths of upholstery off-cuts during a weekend backyard group workshop. Many hands and locations have been involved in the progression of this rope artwork. Initially conceived as an indoor installation, leading the viewer through the nooks and crannies of the previous Gaffa Gallery on Randle Street in Surry Hills. Then titled Ariadne’s Thread referring to the ancient Greek myth of the Cretan Labyrinth navigated using a spool of thread. The journey of the hand-braided rope has continued into the outdoors, coiled from the ground up a poplar tree trunk and disappearing into the upper branches, in the Hunter Valley as Recoiling, part of Sculpture in the Vineyards 2009. Earlier this year it was interwoven into the fence rails forming Heart-beat as though echoing the pulse rates of passing joggers on the Drummoyne Bay Run. In its current incarnation as Escapade, the red hand-braided rope continues to explore navigation of space and boundaries, relating to the concept of Ariadne’s thread as it overcomes obstacles and traces perimeters. The story of Ariadne, her ball of thread and the journey of the labyrinth is an ancient one, which many have become fascinated by and elaborated on, “…many have wandered the labyrinth already. Yet the fascination remains, the challenge is one too tempting to refuse, and the journey is still one well worth making.”[1]

Ariadne was a princess, the daughter of King Minos, living in the palace of Knossos in Crete. A place renowned for a pioneering legal system, but also “…notorious for the bizarre and transgressive acts of some of its inhabitants… a place of extremes and contradictions. Justice cohabits with tyranny, and darkness with revelation.”[2] Underneath the palace there was a complex and deadly maze, built by the master designer Daedalus, to house the Minotaur[3], who fed on the human flesh of Athenian sacrificial victims[4]. When Ariadne fell in love with Theseus, the Athenian prince leading the third sacrificial group, she decided to aid him in surviving the labyrinth. She gave him her ball of thread to fasten to the entrance, to unravel and mark his passage. Then, after killing the Minotaur, he could retrace his way back out of “… the tricks and windings of the building, guiding blind steps with a thread.”[5]. In accordance with Ariadne’s desires, the lovers left Crete and sailed to the island of Naxos. But there on the beach, their romance ended; Theseus abandoned Ariadne while she slept, even though he had promised to marry her in Athens. Angrily she cried out lamenting her fate and cursed Theseus’ ship as it sailed away. The god Dionysus, heard the cries of the forlorn heroine and dramatically descended upon the island in his chariot pulled by cheetahs. He then proceeded to woo, rescue and wed Ariadne himself. As a wedding gift to Ariadne, Dionysus set her crown of stars in the nights sky “as the Cretan Crown, you will often guide a wandering ship”[6].

Ariadne was a princess, the daughter of King Minos, living in the palace of Knossos in Crete. A place renowned for a pioneering legal system, but also “…notorious for the bizarre and transgressive acts of some of its inhabitants… a place of extremes and contradictions. Justice cohabits with tyranny, and darkness with revelation.”[2] Underneath the palace there was a complex and deadly maze, built by the master designer Daedalus, to house the Minotaur[3], who fed on the human flesh of Athenian sacrificial victims[4]. When Ariadne fell in love with Theseus, the Athenian prince leading the third sacrificial group, she decided to aid him in surviving the labyrinth. She gave him her ball of thread to fasten to the entrance, to unravel and mark his passage. Then, after killing the Minotaur, he could retrace his way back out of “… the tricks and windings of the building, guiding blind steps with a thread.”[5]. In accordance with Ariadne’s desires, the lovers left Crete and sailed to the island of Naxos. But there on the beach, their romance ended; Theseus abandoned Ariadne while she slept, even though he had promised to marry her in Athens. Angrily she cried out lamenting her fate and cursed Theseus’ ship as it sailed away. The god Dionysus, heard the cries of the forlorn heroine and dramatically descended upon the island in his chariot pulled by cheetahs. He then proceeded to woo, rescue and wed Ariadne himself. As a wedding gift to Ariadne, Dionysus set her crown of stars in the nights sky “as the Cretan Crown, you will often guide a wandering ship”[6].  Navigation depends almost entirely on one trusting another’s memory, following the directions and markers recalled by others. Similarly, memory was heavily relied on to sustain the ancient Greek myths. For centuries the very existence of these myths relied on the teller’s memory, each time a myth was retold orally, the narrator’s reinterpretation added another layer to the generational embellishment. Ariadne’s thread was a guiding device, overcoming the challenges and shortcomings of memory, as there was almost no way to memorise the paths of the labyrinth. Indeed, Daedalus who designed the labyrinth nearly became lost there himself, “Daedalus filled countless paths with wandering and scarcely himself managed to get back to the threshold: so great was the building’s trickery.”[7] Thus, the ball of thread is also known as a clew or clue – hence a clue to solving the labyrinth.

Navigation depends almost entirely on one trusting another’s memory, following the directions and markers recalled by others. Similarly, memory was heavily relied on to sustain the ancient Greek myths. For centuries the very existence of these myths relied on the teller’s memory, each time a myth was retold orally, the narrator’s reinterpretation added another layer to the generational embellishment. Ariadne’s thread was a guiding device, overcoming the challenges and shortcomings of memory, as there was almost no way to memorise the paths of the labyrinth. Indeed, Daedalus who designed the labyrinth nearly became lost there himself, “Daedalus filled countless paths with wandering and scarcely himself managed to get back to the threshold: so great was the building’s trickery.”[7] Thus, the ball of thread is also known as a clew or clue – hence a clue to solving the labyrinth.

Throughout ancient Greek mythology, Crete is a place where history has a tendency to repeat itself, echoing the winding labyrinthine pathways beneath the ruler’s palace. These Grecian cyclic trajectories are further reflected in the circularities and repetitions that course throughout the entirety of Roman history.[8] Indeed, this metaphor can expanded into more recent history, as the Roman Empire’s insatiable expansion; cycles of wars, destruction and conquests have been repeated in European colonisation around the world. Even today multi-national companies continue to retread similar exploitative paths. It is as though humanity is trapped in persistent cycles of labyrinthine confusion.

However, the use of the thread in the labyrinth also suggests hope. Perhaps this cyclic tendency does not have to ring with finality, lost in inescapable, endless repetition of gloom and doom. If we can see these historical patterns in our contemporary situations and learn from past mistakes, tracking errors and dead-ends, then perhaps some future cycles of catastrophe may be averted. The philosophical writer, Henry Geiger, considers the labyrinth as a metaphor for daily life. Like the Athenian victims who “wander in circles, with no knowledge of how to escape. So do all men and women feel, time and again… But where is the modern equivalent… of the slender Ariadne's thread?.”[9] According to Friedrich Nietzsche life is the labyrinth of the human condition “to affirm human life is to value living within this labyrinth, rather than to attempt to escape from it.”[10] Nietzsche’s writings are rich with allusions to the metaphor of the labyrinth, he saw himself as a digger below the surface, an alchemist who turned suffering into philosophising. He claimed that pain acted as a thread into his labyrinth and helped him to navigate it. Indeed, if one was to give pain a colour, it would probably be red, the colour of my threads.

However, the use of the thread in the labyrinth also suggests hope. Perhaps this cyclic tendency does not have to ring with finality, lost in inescapable, endless repetition of gloom and doom. If we can see these historical patterns in our contemporary situations and learn from past mistakes, tracking errors and dead-ends, then perhaps some future cycles of catastrophe may be averted. The philosophical writer, Henry Geiger, considers the labyrinth as a metaphor for daily life. Like the Athenian victims who “wander in circles, with no knowledge of how to escape. So do all men and women feel, time and again… But where is the modern equivalent… of the slender Ariadne's thread?.”[9] According to Friedrich Nietzsche life is the labyrinth of the human condition “to affirm human life is to value living within this labyrinth, rather than to attempt to escape from it.”[10] Nietzsche’s writings are rich with allusions to the metaphor of the labyrinth, he saw himself as a digger below the surface, an alchemist who turned suffering into philosophising. He claimed that pain acted as a thread into his labyrinth and helped him to navigate it. Indeed, if one was to give pain a colour, it would probably be red, the colour of my threads. Red is the colour of blood. Red is the colour of pain. Red is the colour of violence. Red is the colour of danger. Red is the colour of blushing. Red is the colour of jealousy. Red is the colour of reproaches. Red is the colour of retention. Red is the colour of resentments.[11]

The red thread in the labyrinth is like an umbilical cord, a connection to the beyond, as the salvation of this cord-thread sustains life within the subterranean labyrinth; within mother earth, like a womb. During our lives we each build around ourselves a maze of memory, of hopes and fears, made up of circumstances, experiences, thoughts and emotions. We navigate our way through the world as we find it, in all its multi-layered complexities, possibilities and histories. Despite new ways of articulating our positions, the philosophical questions around the meaning of human existence remain much the same. This is perhaps why these ancient stories continue to ring true and repeatedly reveal layers of meanings to new generations. The Greeks considered living an experience of being in partial bondage but one where “every human experience provides ingredients which may be transmuted with the help of some sort of Ariadne's thread, the whole ‘meaning of life’ should be understood as a progressive series of awakenings.” [12]

The red thread in the labyrinth is like an umbilical cord, a connection to the beyond, as the salvation of this cord-thread sustains life within the subterranean labyrinth; within mother earth, like a womb. During our lives we each build around ourselves a maze of memory, of hopes and fears, made up of circumstances, experiences, thoughts and emotions. We navigate our way through the world as we find it, in all its multi-layered complexities, possibilities and histories. Despite new ways of articulating our positions, the philosophical questions around the meaning of human existence remain much the same. This is perhaps why these ancient stories continue to ring true and repeatedly reveal layers of meanings to new generations. The Greeks considered living an experience of being in partial bondage but one where “every human experience provides ingredients which may be transmuted with the help of some sort of Ariadne's thread, the whole ‘meaning of life’ should be understood as a progressive series of awakenings.” [12][The majority of this essay has been adapted from A thread in the labyrinth, reflecting on Ariadne’s tale, Kath Fries 2008, Sydney College of the Arts University of Sydney, Master of Visual Arts Dissertation: Ariadne’s Thread - memory, interconnection and the poetic in contemporary art, pages 17 to 23. http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/5709]

[1] Armstrong, R. (2006). Cretan women: Pasiphae, Ariadne, and Phaedra in Latin poetry. Oxford; New York, Oxford University Press.

[3] The Minotaur was a ferocious creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull.

[4] A regular sacrifice of seven youths and seven maidens were demanded from Athens, to be fed to the Minotaur.

[10] White, A. (1990). Within Nietzsche’s labyrinth Into the labyrinth, The Risk of Interpretation, New York and London: Routledge.

[11] Qualls, L. (1994). "Louise Bourgeois: The Art of Memory." Performing Arts Journal, 16(3): 39-45.

%2BWhite%2C%2BBRANCH%2B3d.jpg)

.jpg)