|

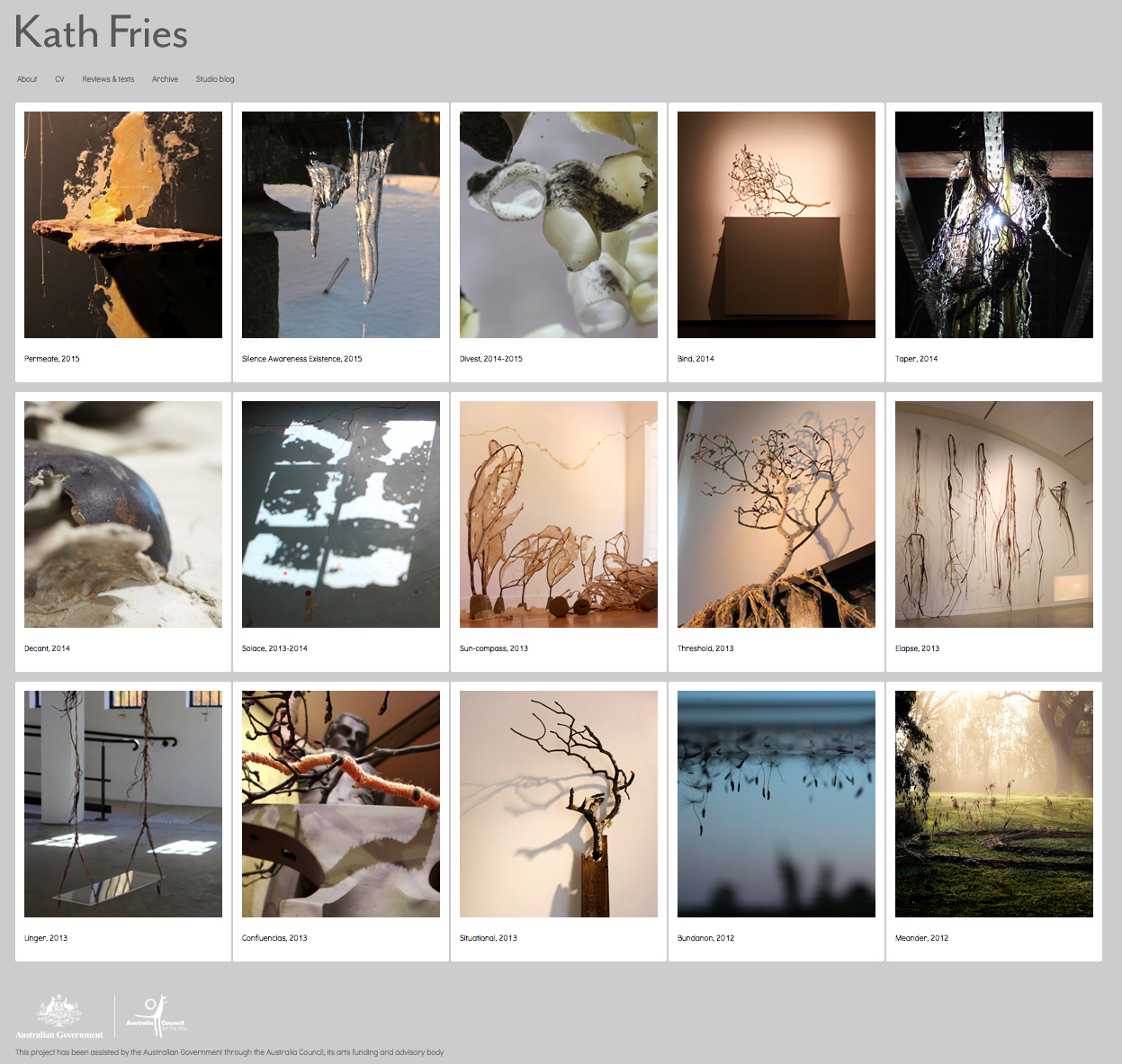

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape i, 2015, photograph |

Last week I drove 900km west from Sydney to the dry ancient lakebeds of Mungo National Park, with artist Shoufay Derz and

musician Emily Rice. As night fell it began to rain heavily and our car slowed

to a crawl, frequently stopping to wait for the thirsty kangaroos and echidnas

drinking from the puddles forming in the ruts of the unsealed dirt road. Around

midnight we settled into our accommodation in the old Shearer's Quarters,

knowing that we would be stranded there for couple of days, as the unsealed

clay roads became boggy, slippery and completely impassable in the rain. After our long journey we were glad to have arrived and not concerned about

having to stay an extra night in this magical, quiet, ancient place. It was a fascinating

place to just be. We were quite lucky to see this wonderful desert landscape in the unusual wet

weather - the last big rainfall was in 2011. There was a significant amount of water, but it was soon

vanquished by baking sunshine and blistering winds, drying the landscape,

vegetation and roads. Then, as each day passed the park rangers re-opened a section of the loop

road so we were eventually able to visit all the main sites and rock

formations.

|

| Kath Fries, Big puddle in Mungo, 2015, photograph |

Mungo is one of the most ancient parts of Australia and

buried in its thick layers of sand and clay is significant evidence of changes

in climate, waters and landforms spanning the last 100,000 years. This geology

is both fragile and robust, quiet and resonant, as the layers of sediment have

washed and accumulated, piling up with narratives of historical time and place.

Dreamtime-stories and scientific-rationality not only meet on these dry

ancient lakebeds, but they coalesce and find common ground. Mungo's layers of

clay have revealed significant evidence of human habitation dating back over

50,000 years across expanses of the last ice age, so Mungo is one of the oldest

places outside of Africa to have been occupied by modern humans since ancient

times. “The ancient Willandra people thrived with the abundance of the lakes,

then adapted to drier, hungrier times of the last ice age and survived to the

present day. Their story can be discovered in the folds of the land, along with

their fireplaces, burials, middens and tools.” (link)

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape ii, 2015, photograph |

As tourists visiting Mungo, we were understandably confined

to the boardwalks, unlikely to recognise or appreciate the subtle traces of these stories in

the land or see the slight differences between ancient mega-fauna fossilised

bones and those of recently deceased kangaroos. Although as artists, we had our

own ways of being receptive and sensitive to the intense and ancient presence

of our surroundings. But it was somewhat difficult to match this with the dry

scientific and pastoral histories conveyed via the information panels and

diagrams of the visitors centre. However, over the course of several

conversations with Tanya - traditional custodian and Mungo

park ranger - the depth, breadth and resonance of the site came alive.

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape iii, 2015, photograph |

Towards the end of our visit, the night skies cleared and we

walked a short distance from the campfire pit and the buildings’ few solar

powered lights, to lie on the road and look at the stars that stretched from

horizon to horizon in every direction, a vast dome around us. For the first

time I could clearly see the Emu - a definitive symbol of Aboriginal Astronomy, which Tanya had described to us earlier in the day. The Emu

isn’t a pattern connecting the stars themselves, but rather the darkness of the

dark dust lines between the dense stars of the Milky Way, which forms the shape

of the Emu and its egg (link). The Emu changes orientation and shape somewhat with the

seasons and these changes tell Aboriginal people the correct time to collect

emu eggs. During the daytime, we saw about eight wild emus, flouncing their

fabulous long tail feathers running through Mungo’s saltbush and scrub. Tanya

told us that the ones we saw were female, as at this time of year the males are

sitting on the nests minding the eggs.

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo clay and sand patterns, 2015, photograph |

At night sitting outside around the warm smoky campfire-pit,

under those stars, sharing stories with other visitors staying at the Shearer’s

Quarters, I felt the prickling’s of a spooky presence watching over

our shoulders from the vast dark landscape around us. Indeed there were ancient

burial grounds not far away. Famously 40,000-year-old remains of a woman were

discovered at Mungo, in 1968. Dubbed the ‘Mungo Lady’, she is the oldest

demonstrated ritual cremation anywhere in the world. She is a crucial ancient

link to the rituals and emotions of people living in this area so long ago, and literally embodies the importance of death and grieving that remains so core to our

understanding of what it is to be human. The 'Mungo Lady's' bones were exposed by erosion, so she wasn't as much discovered as revealed, a gift from the land and the spirits. Her bones were taken from Mungo by the archeologists, but after considerable lobbying from local Aboriginal groups, she was returned to the area and her continued

presence is immensely profound. I was fascinated to hear from Tanya, that her

Nana had been a key spokesperson in the negotiations and respectful handling of

this delicate and sensitive episode, making clear that ‘Mungo Lady’ is her

ancestor and part of her family. This strong interconnection with people, place

and past continues to be very powerfully felt, and the sense of the 'Lady’s' spirit watching over the Mungo region permeates how all humans – visitors,

scientists, archaeologists, locals and traditional owners – engage with this

ancient site.

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape iv, 2015, photograph |

More recently, in 2003, ancient perfectly preserved human

footprints were revealed beneath the shifting sands of Mungo. The twenty-five

trackways are about 20,000 years old, the oldest footprints ever found in

Australia and the largest set of Pleistocene ice age footprints in the world. After

being thoroughly documented and researched by the traditional owners, scientists

and archaeologists, the trackways were then considerately reburied. It would be

impossible to try and remove the imprints or leave them uncovered, if they had

been left exposed to the elements, animals and humans, the trackways would

have quickly disintegrated. It was agreed that the best place for these

precious records to be kept was in the exact same environment that has

preserved them for so long. I think there is something poetically wonderful

that these extremely valuable treasures have been reburied with only an 'X' marking the spot on the geophysical maps and in people's memories who can read the land. (link)

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape v, 2015, photograph |

The fragile shifting surface of Mungo is like a constantly

changing skin, growing and shedding, rising and falling, which contains and

protects the powerful vitality of resilience and presence beneath. To feel the abrasive

sandblasting wind blowing against my face as it skidded across Mungo’s clay layers, and witnessing the alarmingly quick way that the exposed

clay dissolved in the rain, was an evocative experience of impermanence. Reflecting on what I could not see, but had been told, about the burial grounds and ancient bodily remains of humans and animals

contained and protected within the clay, then briefly whisked to the surface to

see the light of day in my own lifetime, conjures further notions

of embodied existence and interconnection between the known and unknown. Aboriginal elders, scientists and archaeologists agree that there

are even more fossils, trackways and precious ancient history hidden within the

layers of clay.

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo Kangaroos, 2015, photograph |

Today, Mungo is a landscape that reveals its history in

its own time, rather than people purposefully setting out to dig it up. The

land and weather have their own agency, timeframe, purposefulness and ways of responding. Traditional custodians and Aboriginal Elders are teaching visitors and scientists that there are

certain ways of patiently listening to the land and learning from it. I feel fortunate to have

experienced a mere inkling of the traces of history and presence in the

landscape at Mungo, which was quite profound, effecting and unique to that place.

|

| Kath Fries, Mungo landscape vi, 2015, photograph |

The dissolving rains and buffering, blistering winds that

sandblasted my skin – as well as the surface of the land, emphasised how easily

this ancient, fragile and robust environment changes. There were many nuances in

my personal present-time encounter with Mungo, the sense of constant gradual

changes and shifts, being traced and imprinted on the surfaces of the

landscape, feel like they have also left an imprint on me.

%2BWhite%2C%2BBRANCH%2B3d.jpg)

.jpg)