Something really does happen to people who go north—they become at least aware of the creative opportunity which the physical fact of the country represents and come to measure their own work and life against that rather staggering creative possibility: they become, in effect, philosophers.[1]

The renowned Canadian pianist Glenn Gould had a lifelong fascination with the idea of North. The sheer physical profundity of the northern land was for Gould a unique opportunity to observe the concept of solitude. This is not exclusive or prerogative to those who go north, but it does appear that this environment leaves its marks upon those who make the journey. There is consciousness that arises from an engagement with these northern landscapes, a heightened phenomenological spatial awareness of one’s own body in space—often inducing an enhanced perception of nature, with all its transcendent otherness. Kant famously ruled that ‘it is the disposition of soul evoked by a particular representation engaging the attention of the reflective judgement, and not the Object, that is called sublime’. There is a long held belief amongst northerners that life-wisdom is not found in social interaction or cultural centres, but rather in solitary confrontation with nature at its most extreme. It is amongst nature that one must seek true self.

The Nordic countries are as geographically remote and topographically as

different as can be to Australia. There

is a Lutheran sensibility that lives in these northern lands, where

historically nature dictates the terms of human existence and creates a

dependence on the surrounding environment.

This

connection to place and the landscape is an important marker of a Nordic

identity. Modern Nordic societies might be changing, but nature still has a

constant presence in their various national psyches. Nature is for these people

what cultural historian Nina Witoszek calls a ‘perpetuum mobile’—a semiotic

centre around which everything moves.

We speak of the four seasons, yet in the north one tends to speak of only two, summer and winter, the rest is morphological/transitional in-between time. There is a sense of deep mourning as autumn descends, a prelude to what for some seems like a long, bleak and foreboding time ahead, filled with melancholy and isolation. Yet, for many, this dark time is a period for self-reflection and askesis. Askesis is an embedded belief that the light must be balanced with the dark to truly understand one self.

This darkened temporal - Out of Time - space frequently destabilizes visual perception, blurring the lines between the real and the imagined. As darkness descends on the land, new shapes appear in the shadows. Winter takes hold. A diffused whiteness that blends one thing into another – the sky becomes part of the ocean and it all becomes part of the weather. This distorted, yet hyper-real state of being, provokes a subconscious connection to nature and the landscape around. The great forests with the deep lakes, windswept rugged coastlines, and tall mountains filled with waterfalls and rivers, are traditional places, often depicted in the rural Nordic folk culture, believed to be home to subterranean supernatural forces. In Norwegian Folktales, Pat Shaw recounts Erik Werenskiold’s description of his childhood home:

One sat in the darkness by the oven door … from the time of the tallow candle and the rush light … in the never-ending, lonely winter evenings, where folk still saw trolls and captured the sea-serpent, and swore that it was true.

But with spring comes the longed for release from the darkness, and as winter slowly dissolves, the mood lifts and all the senses are filled with the prospect of endless summer days. The Swedish writer August Strindberg once declared that summer is the season when ‘in all the countries in the North, the earth is a bridge and the ground is full of gladness’. This light-dark dichotomy, with all its atmospheric conditions generates an environment that provokes us to ask: how do you feel the weather, the landscape or a place?

Ellen Dahl, April 2016

Ellen Dahl grew up in Hammerfest in Norway, and moved to Australia in 1995. Dahl is an artist, photographer and writer, working with and around the landscape, exploring junctures of identity with a physical, political and psychological sense of place. ellendahlphotographer.com

[1] ‘The Idea of North: An Introduction’ The Glen Gould Reader

|

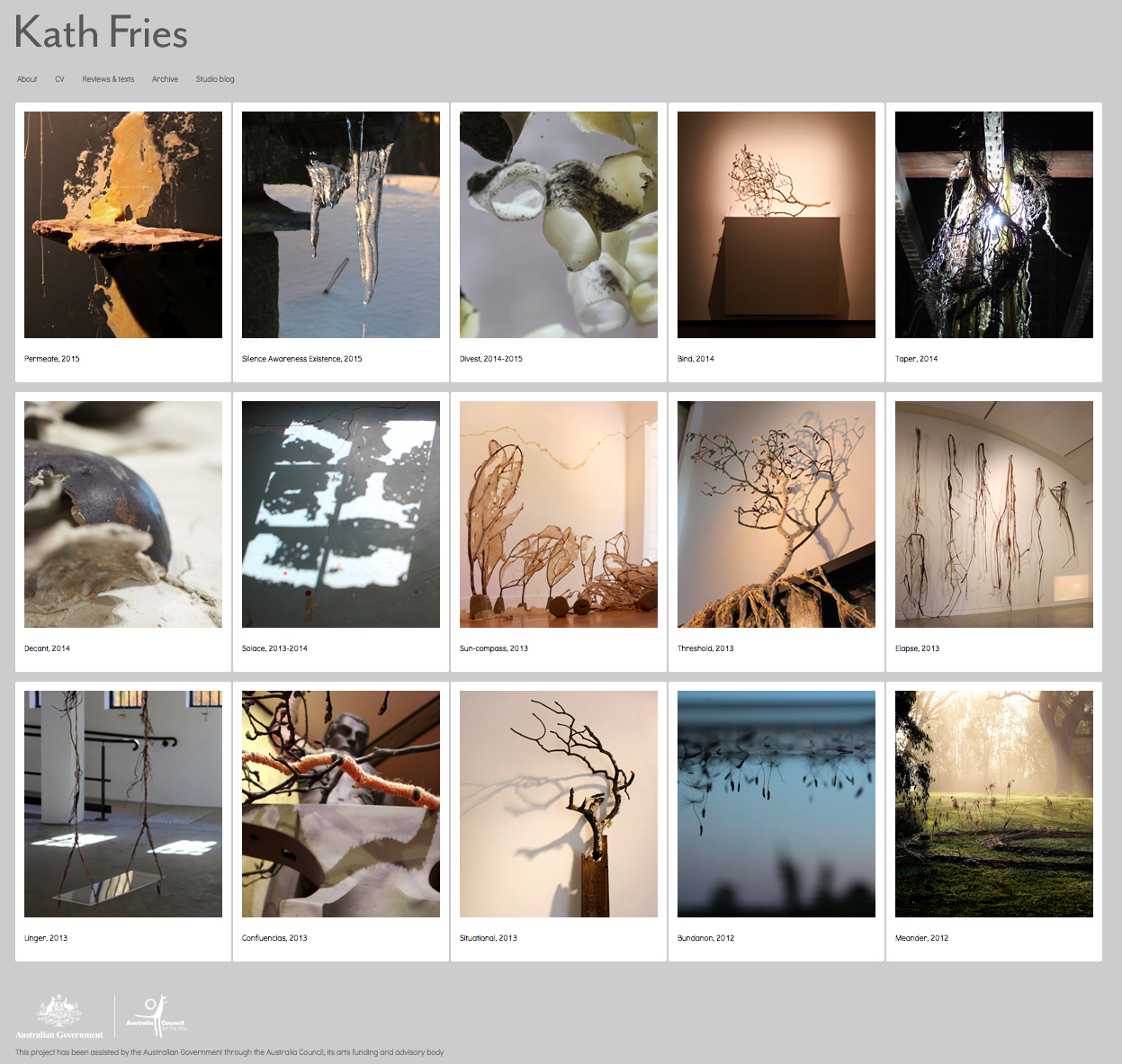

| Out of Time, May 2016, AirSpace Projects, gallery view of work by Kath Fries and Michelle Heldon |

Out of Time

6 - 21 May 2016

Michelle Heldon, Taryn Raffan and Kath Fries

Michelle Heldon, Taryn Raffan and Kath Fries

Gallery one, AirSpace Projects

10 Junction St, Marrickville NSW

During their residencies in Greenland, Iceland and Finland, the

artists were drawn to the pull of the magical, inner power of the landscapes

and story-telling traditions of the far north. The terrains of these Nordic countries

continue to resound with narratives, mysterious secrets and silences, frozen

and forested gifts and perils. Michelle Heldon, Taryn Raffan and Kath Fries works in Out

of Time conjure an age-old instinct to wander, to experience seasons and

environments, and to relate surreal findings back to the familiar. These poetic

visual stories are transported, blended, reconstructed and adapted into

contemporary understandings of existence and open-ended imaginations.

|

| Out of Time, May 2016, AirSpace Projects, gallery view of work by Taryn Raffan and Kath Fries |

%2BWhite%2C%2BBRANCH%2B3d.jpg)

.jpg)